Hrvatska šestorka, čiji su pripadnici u najduljem kaznenom procesu u povijesti Australije osuđeni na 15-godišnje kazne, unatoč toga što sumnja u pravednost sudskog procesa i krivicu osuđenih nikad nije prestala kopkati australsku savjest, trebalo je “sačekati” 40 godina i današnjih dana, da bi se istina mogla konačno, kroz hrpu laži, obmana i manipulacija, prokopati do površine.

Slučaj Hrvatske šestorke, pretpostavljam, već dugo godina ne predstavlja nepoznanicu Hrvatima u Domovini. Bilo je to 1981., deset godina prije hrvatskog osamostaljenja i početka Domovinskog rata i deset godina nakon gušenja Hrvatskoga proljeća, u vrijeme kad je težnja za hrvatskom samostalnošću među brojnim hrvatskim iseljeništvom u Australiji dostigla Celziusov kipući stupanj i kada je jugoslavenski državni aprat pronašao dodirnu točku s dijelom australskog prinudnog sustava u zaključku da Hrvate treba hitno i na svaki mogući način obuzdati. Hrvatski aktivizam je, kako je to meni osobno bilo nekoliko puta rečeno u obliku prijetnje, narušavao odnose s jednom prijateljskom zemljom.

Jugoslaviji, da bi provela obračun s hrvatskom antijugoslavenskom emigracijom, nije trebalo zadovoljavati nikakve zakonske uvjete. Ona je već godinama po zapadnim državama prakticirala ubojstvima eliminirati svoje protivnike. Da bi se našli na poziciji zajedničkog interesa i zadovoljili australski zakonski okviri za obračun s Hrvatima, hrvatski aktivizam je trebalo pretvoriti u terorizam, po mogućnosti na što većoj skali, čemu nije bilo primjera u stvarnosti, pa ga je trebao inscenirati. Tako je u beogradskoj kuhinji jugoslavenskog terorizma stvoren scenario hrvatskog terorizma na tlu Australije, kako bi se protiv Hrvata pokrenuo australski prinudni aparat.

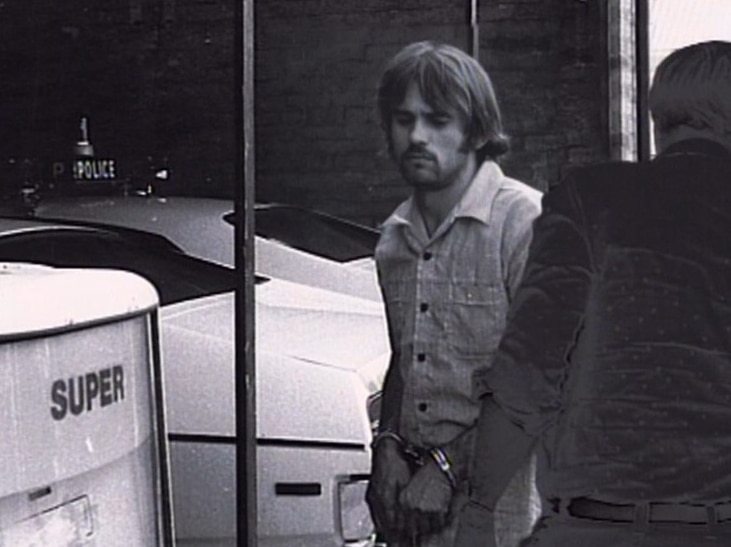

Koristeći agenta provokatora Vitomira Misimovića pod lažnim imenom Vico Virkez, kreirane su circumstancialne okolnosti (lat. – indirektne smjernice prema nečijoj krivici bez konkretnih dokaza) i na osnovu lažnih informacija o grotesknim terorističkim planovima, iza rešetaka se našlo šest australskih Hrvata: Ilija Kokotović, Josip Kokotović, Mile Nekić, Vjekoslav Brajković, Maks Bebić i Ante Zvirotić. Od njih sam kroz godine prije toga, kroz aktivnost Hrvatske republikanske stranke u Australiji, poznavao Milu Nekića i braću Kokotović. Na sudu se zajedno s njima našao i agent provokator Virkez, koji se u procesu pretvorio u informatora i nakon izvršenog zadatka našao oslobođen i poslan natrag u Jugoslaviju odakle je i došao.

Šestorica su u najduljem kaznenom procesu u povijesti Australije osuđena na 15-godišnje kazne i unatoč toga što sumnja u pravednost sudskog procesa i krivicu osuđenih nikad nije prestala kopkati australsku savjest, trebalo je “sačekati” do današnjih dana, da bi se istina mogla konačno, kroz hrpu laži, obmana i manipulacija, prokopati do površine.

Ključni broj je 40. Naime, nakon 40 godina, slučajevi ove vrste u Australiji bivaju deklasificirani i žig tajnosti se skida s dokumenata koji su sakriveni stajali u mračnim pravosudnim arhivama.

Anatomija nepravde

Počelo je s knjigom “Anatomy of Injustice – Australian Croatian Six Case Up For Judicial Inquiry 40 Years On” australskog istraživačkog novinara Hamisha McDonalda “Osnovana sumnja: Špijuni, policija i Hrvatska šestorka” (2019.), što je na stranicama Projekta Velebit već opisano u tekstu Ine Vukić, 7. ožujka 2021. “Anatomy of Injustice – Australian Croatian Six Case Up For Judicial Inquiry 40 Years On”

Najveći australski pravni pobačaj

U svibnju ove godine ABCRN Nacionalni radio objavio je jednosatni radio-program na ovu temu. U emisiji gosti su bili Lydia Peraic, Max Bebic, Jim McCrudden, Ian Cunliffe, Sasha Uzunov, David Buchanan, Chris Masters i Hamish McDonald.

Ovdje bi htio istaknuti australskog istraživačkog novinara makedonskog porijekla Sašu Uzunova, s kojim sam jedno vrijeme surađivao, a koji je veliki dio svog istraživačkog rada posvetio zadovoljenju pravde za Hrvatsku šestorku. Treba također naglasiti da smo kao HDP održavali blisku suradnju s makedonskim pokretom za osamostaljenje, jednako kao i s pokretom kosovskih Albanaca.

Emisiju pod naslovom “Australski najveći pravni pobačaj” možete poslušati OVDJE.

Nakon toga, vodeći australski dnevnik The Australian započeo je objavljivati seriju tekstova od kojih prva dva možete pročitati u nastavku.

Prvi je iz pera Shirley Stedul, koja povezuje dva slučaja vezana uz australski sustav pravde, slučaj Hrvatske šestorke i slučaj Nikole Štedula, nerazdvojno vezan uz Australiju i njezine odluke koje su se kasnije reflektirale na njegovu sudbinu.

Drugi je napisao Gerard Henderson, prominentni novinar i direktor Sydney instituta.

Na žalost, ovdje prestaje hrvatski tekst i počinje engleski, jer ja jednostavno nemam vremena prevoditi toliki materijal. Onima koji ne barataju engleskim, žele li ga pročitati, preostaje Google-ov virtualni prevoditelj.

Renewed hope for justice in case of Croatian Six

The appointment of a new judge is a sign of hope for the Croatian Six, now in their 70s, that justice may be within reach. The six men, their families and the Croatian-Australian community deserve to be given a “fair go” – as is the Australian way. It’s time for the law and truth to prevail.

The Australian 25 August 2022, by Shirley Stedul

On February 8, 1979, six young Croatian-Australians were arrested in Lithgow and Sydney and charged with conspiracy to commit acts of terrorism in Australia.

What followed was not only the longest-running criminal court case in Australia but, since new evidence has come to light, the so-called Croatian Six case is seen as one of the most serious miscarriages of justice in Australian legal history.

Although all six men persistently pleaded their innocence, and evidence presented in court was weak, some of it extracted as a result of police brutality, in 1981 all six men in the dock were found guilty as charged and each was sentenced to 15 years in prison. Their appeal was dismissed.

Despite previous failed attempts, Sydney barrister Sebastian De Brennan and solicitor Helen Cook, acting pro bono, recently made a third application to review the case.

The NSW Supreme Court has now designated judge Robertson Wright to look at their application. Justice Wright is expected to make his findings known before the end of this year. With some 5000 pages in 20 volumes of trial transcript he has much work to do.

Given past rejections for a review, the appointment of Justice Wright has provided hope within the Croatian community that a genuine breakthrough may be forthcoming.

Prior to the 1991 break-up of the federation of Yugoslavia, a constant, no-holds-barred war was being waged by the Yugoslav secret police, Uprava Drzavne Bezbednosti (UDBA), to prevent the disintegration of the failing federation into its constituent republics. UDBA had a “licence to kill” if that’s what it took to achieve that aim. The Yugoslav secret police not only severely persecuted those in Yugoslavia who advocated independence and freedom from Josip Tito’s brand of communism, but similarly targeted those who had gone to live in other parts of the world.

The long arm of UDBA reached into Australia, where it conducted a series of campaigns, including “false flag” acts of violence, in order to brand the Croatian-Australian community as “extremists” and “terrorists”. UDBA also used murder to silence those engaged in legal political work in democratic nations, including Germany and the US.

John Schindler, a former specialist on Balkan issues with the US National Security Agency, described UDBA’s involvement in the case of the Croatian Six as “one of its “great successes”, so devastating was it not only to the lives of the six men, but the whole Croatian-Australian community.

In an ABC Four Corners documentary filmed in 1991, reporter Chris Masters tracked down Vico Virkez, the chief crown witness against the Croatian Six. His real name was Vitomir Misimovic. Having fled Australia on a Yugoslav passport before the end of the trial, he was then living in Jablanica, in the Gradiska municipality of what is now the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In the Four Corners interview, Misimovic openly admitted that he had provided false testimony in court under instruction from NSW police. He said that he had been warned of serious consequences if he failed to obey them.

However, in 1994, Misimovic’s own admission was not considered sufficient evidence for the Croatian Six to be granted an application for a review of the convictions.

Former federal government lawyer Ian Cunliffe warned that crucial evidence about UDBA activities had been withheld from the trial. Evidence of systematic abuse of the legal process by the NSW police units was also disregarded. Of note, Roger Rogerson, who led one arresting team, was later imprisoned for serious crimes, including murder during the course of a drug deal.

In his book, Reasonable Doubt: Spies, Police and the Croatian Six, published in 2019, Australian journalist Hamish McDonald drew on ASIO files from the National Archives of Australia. They show ASIO had been monitoring Virkez/Misimovic, who was associating with a known UDBA officer at the Yugoslav consulate-general in Sydney for several months prior to the arrests while masquerading as a Croat nationalist within the Croatian community.

NSW police were told of the ASIO findings; however assistant police commissioner Roy Whitelaw told ASIO that if this information got to the opposition, meaning the defence lawyers, it would “blow a hole in the police case”. The information was withheld, and the jury was assured by the crown that there was “not a skerrick of evidence” that Virkez/Misimovic was working with the Yugoslav intelligence service.

Paths cross

As a young Scottish-Australian migrant living in north Queensland, I met and fell in love with a Croatian-Australian called Nikola Stedul in the mid-1960s. By the time I met Nikola, he had become a naturalised Australian citizen. He had fled Yugoslavia illegally as a political refugee with a qualification in plumbing and sheet metal working, but like many young migrants who came to Australia he was able to turn his hand to a variety of jobs, including heavy manual labour, farming and mining.

He was also a thinker and a dreamer. His dream was that one day Croatia would become, through democratic means, an independent state that would prosper in accordance with international democratic laws. Quite simply, he wanted for his people the same freedom, human rights and privileges he had discovered and cherished in Australia.

It was for this reason too that he joined the CMF (Citizen Military Forces). The Vietnam War was raging and Nikola felt the need to prepare to partake in Australia’s defence if called upon.

At that time, ASIO officers routinely visited Yugoslav migrants, including Croats such as Nikola, due to ethnic clashes, especially during football matches and political protests. We learned that the federal police also questioned Nikola’s membership of the CMF. This was my husband’s first experience of targeted discrimination by Australian authorities.

Our ASIO “visitors” later told us that they had been tipped off by Yugoslav dispatches, as well as complaints from local Yugoslav sympathisers, that Nikola was involved in Croatian political activities. “But,” one of the visitors added, “bombs have gone off in Sydney, and there have been armed incursions into Yugoslavia involving Croatian-Australians.”

No escape from past

Although Nikola’s CMF commander explained that his involvement in political activities was legal in Australia, and was not grounds for discharge, Nikola decided that his motives would always be unjustly questioned and so reluctantly discharged himself on principle. After selling our farm, we went to Europe with our two little girls to spend some time with Nikola’s family. When it came time to renew his Australian passport, however, he was told by Australian authorities that it was being withheld.

He was offered a limited travel document that would enable him only to return to Australia, but Nikola saw this as a violation of his basic rights. He sought explanations, but none were forthcoming. He offered to return if he would be assured of the chance to answer to any charges against him, but was told there were none. He was further informed that they were not obliged to provide any reasons for refusing him a passport since the decision had been made at the “minister’s discretion”.

We later learned that it had been decided that “it was not in Australia’s interest to facilitate the travel of Nikola Stedul”.

With six months remaining on his passport, we were still able to travel to Scotland to meet my relatives as originally planned.

We remained in Scotland during the 17 years that Nikola continued to pursue the renewal of his passport. In true Kafkaesque bureaucratic circularity the continued refusal to grant him his passport was later used as a reason to deny his numerous requests for British citizenship.

He then asked to be written out of his Australian citizenship, but was told that was not possible as he would then be rendered stateless. He explained that this was what he needed in order to take the Australian government to the International Court of Human Rights to highlight the discrimination against Croatian-Australians. Needless to say, this did not alter their decision.

Only in 2002 did he finally accept the limited travel document to return to Australia for the birth of our first grandchild. While we were there he went to Canberra seeking answers as to why he had been subject to discrimination for so many years. The files he sought were “not available, and would not be for a long, long time” he was told. Soon after this trip to Canberra he was finally granted an Australian passport. Yugoslavia no longer existed and Croatia was independent.

Assassination attempt

In Scotland, in 1988, while Nikola was studying as a mature student for a master’s degree in politics and philosophy at Dundee University, he was targeted outside his home in Kirkcaldy in a Yugoslav UDBA assassination attempt.

The six bullets that hit him, two full in the mouth, were an attempt to silence him. His survival was deemed “miraculous” by the surgeon who removed one of the other bullets from his chest.

A neighbour noted the number plate of the hire car used by Nikola’s would-be assassin, Vinko Sindicic. Sindicic was arrested at Heathrow Airport, having taken a flight from Edinburgh to London that morning.

He was taken back to Scotland, where he stood trial, was found guilty and imprisoned for 10 of the 32 years originally handed down by the court.

The shooting and trial were known as the case of the Yugoslav Hitman, which was the title of the Scottish television docudrama made about the shooting. It was the first time a Yugoslav secret agent had been exposed in the UK.

As the defendant, Sindicic said in court, he did not have to prove anything.

He used the well-established UDBA technique of slander and lies to accuse Nikola of instigating with him every manner of conspiracy, including planning to smuggle guns to Scotland and scheming to blow up an airliner. When, after two weeks of evidence, Sindicic was found guilty, he proceeded to accuse the entire Scottish legal system, the police, the doctors and their NHS teams, as well as court witnesses, of being involved in a monstrous conspiracy against him, by claiming that Nikola had not even been shot.

Unanswered question

Whether Sindicic played any role in the Croatian Six saga is a pertinent question, since in preparation for his trial in Scotland he told his lawyer that he had met Nikola in 1978 in Australia.

When the lawyer realised that this could not be true since we had left Australia five years earlier and were unable to return, he dropped this line of defence. However, it begs the question: was Sindicic in Australia in 1978? And why would he want to suggest Nikola was also there then?

The Australian government white paper on counter-terrorism issued in 2010, which covers all terrorism attacks and failed terrorist plots in Australia dating back to 1970, makes no mention of the Croatian Six case. Furthermore, in ASIO’s entry about the Croatian Six case in the agency’s official history, the authors state that the six men were victims of “wrongful conviction”.

The appointment of a new judge is a sign of hope for the Croatian Six, now in their 70s, that justice may be within reach. The six men, their families and the Croatian-Australian community deserve to be given a “fair go” – as is the Australian way. It’s time for the law and truth to prevail.

Coincidence and the troubling case of the Croatian Six

The Australian 26 Aug 2022, by Gerarad Henderson.

It’s one of the best known exchanges in the history of Australian cinema. In the 1994 film Muriel’s Wedding, the character Bill Heslop (played by Bill Hunter) is having an affair with Deidre Chambers (Gennie Nevinson). A planned assignation at the Chinese restaurant has a seemingly surprised Chambers declaring: “Bill!” Whereupon Bill replies: “Deidre Chambers – what a coincidence.”

There are, however, real coincidences. It so happens that the National Archives of Australia recently released a file of 252 documents relating to the convictions of six Croatian-Australians.

The men – Maksimilian Bebic, Mile Nekic, Vjekoslav Brajkovic, Ilija Kokotovic, Joseph Kokotovic and Anton Zvirotic – were convicted concerning a number of offences involving making and stealing explosives. After deliberating for around 70 hours, a jury in NSW brought down a guilty verdict on February 9, 1981, for what became called the Croatian Six.

The jury was convinced beyond reasonable doubt that the accused had conspired to bomb two travel agencies in Sydney run by Serbian-Australians, a theatre in the Sydney suburb of Newtown along with Sydney’s water supply.

There have been doubts about this verdict extending back decades. At the time, Croatia was part of the federation of Yugoslavia, the largest entity of which was Serbia. Yugoslavia was a brutal communist dictatorship essentially controlled by the Communist Party of Serbia, led by Josip Broz Tito.

There is no doubt that many Croatian-Australians in the 1960s and ’70s were intent on overthrowing Tito’s regime. Some even entered Yugoslavia to engage in civil war against Tito’s Belgrade-based regime.

However, there was concern in Australia that bomb attacks on or near Yugoslavia consulates in Melbourne and Sydney were the work of Tito’s secret police aimed at discrediting his Croatian enemies in Australia. In other words, what are called false-flag attacks.

Suspicion was raised because the bombings of Yugoslav properties in Australia involved little damage and few casualties but caused considerable reputational damage to the Australian-Croatian community.

At the time the Croats were seen as anti-communists and Catholic. The left in Australia, led by Labor Party left-wing activists Lionel Murphy and Jim Cairns, disapproved of anti-communists.

Moreover, half a century ago there was still a presence in Australia of what historian Paul Collins in 2017 called “the unconscious elements of anti-Catholicism that has been the default position of Anglo-Australian culture since the 19th century”.

In 2019, former Sydney Morning Herald journalist Hamish McDonald’s book Reasonable Doubt: Spies, Police and the Croatian Six was released by Doosra Media. It does not make for easy reading but it is one of the most important works published in Australia this century.

Reasonable Doubt begins with the initial raids on members of the Croatian Six in February 1979. The raids were led by NSW Police detective-sergeant Roger Rogerson, who currently is serving a term of life imprisonment for murder.

As it turned out, there was scant evidence to support the charges laid by NSW Police. In the event, the accused were convicted on the basis of what the prosecution said were admissions.

Three of the six refused to do a signed interview and police presented records of what allegedly had been said.

There was one typed statement that was unsigned and one man signed a statement but claimed he did so after being assaulted. The statement of the sixth man was ruled inadmissable by the trial judge, who was not convinced it was voluntary – his body was found to be bruised.

In Reasonable Doubt, McDonald makes a convincing case that the trial judge, Allan Victor Maxwell, was hostile to the accused during the trial and in his address to the jury.

However, the verdict was upheld by the NSW Court of Appeal and the High Court of Australia declined to grant leave to appeal. Before the publication of Reasonable Doubt, there had been several applications in the early 1990s to the NSW government to inquire into the safety of the convictions.

Then in 2012 the Supreme Court appointed Acting Judge Graham Barr to reconsider the case – he dismissed the application. Now another report is being undertaken by a NSW Supreme Court judge who will hear submissions from the applicants’ legal representatives along with the Crown advocate. This is currently under way.

And here’s the coincidence. In writing Reasonable Doubt, McDonald got access to some documents on the case prepared by ASIO. However, in recent days, the NAA released ASIO’s detailed files on the case – which include one crucial document.

This was reported in The Australian this week by Jacquelin Magnay (Wednesday) and Stephen Rice (Thursday).

Apart from dubious confessions, the only other substantive evidence against the Croatian Six was the testimony of police informer Vico Virkez, who claimed to be Croatian.

Ian Cunliffe, a senior adviser in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in February 1981, expressed concern that the prosecutor in the Croatian Six case told the jury “there is not a skerrick of evidence that Virkez is a foreign agent”. Cunliffe wrote that this was false – ASIO knew he was an agent of Tito’s secret police. Cunliffe was overruled by his senior officer, JD Enfield.

As early as August 1991, Chris Masters interviewed Virkez in Yugoslavia. Masters reported that Virkez told him that he was, in fact, Serbian and had reported to the Yugoslav regime in the ’70s. Masters also said Virkez claimed to have been coached by NSW Police with respect to his evidence against the Croatian Six.

Alas, the authorities in Sydney and Canberra took little notice of this report.

In his official history of ASIO, The Protest Years, published in 2016, John Blaxland came to a similar view to that proclaimed by some Australian anti-communists decades earlier – namely, that the terrorism that took place in Australia in the ’60s and ’70s was conducted by Serbian communist false-flag operatives.

On available evidence, enhanced by the release of ASIO’s files, the Croatian Six were improperly convicted – an injustice that has done enormous harm to Croatian-Australians over the years and that remains unresolved today.

Gerard Henderson is executive director of the Sydney Institute. His Media Watch Dog blog can be found at theaustralian.com.au

Photo: The Croatian Six – Max Bebic, Vic Brajkovic, Tony Zvirotic, Joe Kokotovic, Ilija Kokotovic and Mile Nekic.